By Keith Bowers

For The Corvallis Clinic

Those of us who don’t work in health care might never consider the importance of radiology until we or a loved one need an X-ray, a CT scan, an ultrasound procedure, or an MRI scan. Yet radiology in all its forms is nothing short of crucial in diagnosis and treatment.

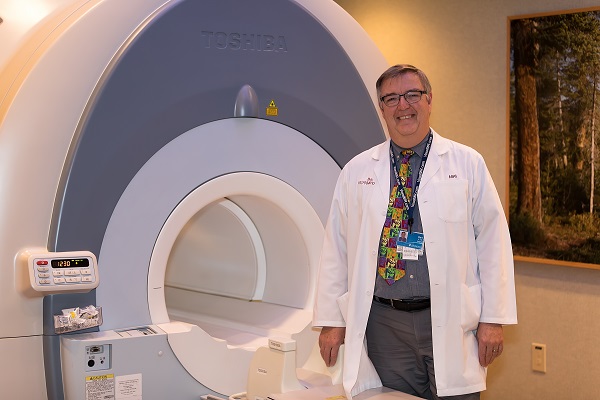

Bart Pierce stands next to the MRI machine at The Corvallis Clinic, where he is an MRI technologist. Pierce, the director of RAD-AID Ethiopia, traveled to Ethiopia to train providers at the Black Lion Hospital in Addis Ababa.

“There’s hardly any diagnosis made without some type of imaging,” said Bart Pierce, an MRI technologist at The Corvallis Clinic Imaging Department.

Of course Pierce was speaking about developed countries such as the United States. Radiology is rare in many Third World nations. One such place is Ethiopia. Until recently, the capital city of Addis Ababa – a city of about 4.6 million – had only a single MRI machine, Pierce said.

By comparison, he said, Corvallis has three, while there are probably six in the Corvallis-Albany-Lebanon area and dozens in Portland – cities whose combined population is less than 1 million.

The absence of radiology has drastic consequences. As many as 4 billion people worldwide are at risk for health problems and death that could be avoided if radiology were available, according to RAD-AID International, a nonprofit group that aims to improve radiology in underserved regions of the world via education and training.

As examples, RAD-AID cites infants lost to complications that could have been avoided using ultrasound, deaths from breast cancer that could have been detected with mammography, and limbs that could have been saved after trauma if X-rays had been available to identify fractures.

To help offset this imbalance, Pierce traveled to Ethiopia last spring. His mission? To train providers at the 800-bed Black Lion Hospital in Addis Ababa where an MRI system had recently been installed. Pierce, who attended Oregon State University, has worked in radiology since 1986 and with MRI technology since 1988. He is also the director of RAD-AID Ethiopia.

The three-week trip was filled with contradictions, to say the least, starting with some negative surprises.

“It Was Like Rush Hour All The Time”

Pierce’s hotel was located near Black Lion Hospital in a poorer section of Addis Ababa. “It was owned and staffed by a group of wonderful Ethiopians who treated me like family,” he said.

An MRI technologist views an image at Black Lion Hospital. Until recently, Addis Ababa, with 4.6 million people, had only a single MRI machine, Pierce said.

While he said he never feared for his safety, he was overwhelmed at the crush of people and volume of activity.

“It was like rush hour all the time,” he said.

Pierce described streets filled with cars and sidewalks lined with people – some walking, some standing, some sitting or lying down. He said the hospital was just as crowded.

“It was the same thing, but the people were all sick,” he said. “In radiology we literally had to push people aside to walk down the hallway.”

Another negative surprise was the lack of ability to communicate, even though many Ethiopians speak English.

In the U.S., “there are signs for everything: where to go, what to do, what not to do,” Pierce wrote in a RAD-AID report covering the trip. In Addis Ababa, however, “I found very few signs, and the ones there, I couldn’t read [because they were not in English.] At the airports there are no itineraries, just announcements that you can’t understand.”

Communication with his family back in Oregon was also problematic. The Ethiopian cell phone system is excellent, he said, but calls to the U.S. are very expensive, and not all American phones work there. Internet-based video services such as Skype are an option, but stable web connections are nearly as rare as radiology equipment.

Pierce described the technology at Black Lion Hospital as lacking, too.

“Infrastructure and IT issues occur daily,” he wrote in his report. “Power is problematic even though a backup generator is in place. It seldom kicks on at the appropriate time.”

Transformative Experience

Pierce admits to having second thoughts about the endeavor, wondering whether he had what it took to see it through. But soon, positive surprises turned things around and contributed to a transformative experience for him and Black Lion Hospital’s radiology department.

He found the technologists proficient in running the machine; they had received some training from the company that installed it, and some of them had worked on the other local MRI system at a private facility.

What’s more, working 12-hour days alongside the radiology staff, Pierce found them well trained, professional and hardworking.

“The technologists who I worked with were just phenomenal,” he said. “I would have brought any of them home with me. They were as knowledgeable and professional as any techs I’ve ever worked with.”

They also showed remarkable hospitality and generosity: “The technologists here took me in and treated me like family. I have never been so well taken of and so appreciated.”

For example, one day Pierce got sick with a gastrointestinal bug, so he missed a shift at the hospital. Upon his return, the technologists were unhappy with him – not because he’d been out, but because he failed to contact them so they could arrange to take care of him.

Training and Equipment Goals

Pierce’s long list of objectives included increasing the staff’s MRI knowledge, training them to apply that knowledge and evaluating safety practices. It turned out to be on-the-job training, as the machine had a flood of patients to serve. Pierce explained that most people in Ethiopia don’t see a physician for what we consider routine things, but only for disorders that render them unable to work or function.

“By the time they get there,” Pierce said, “whatever is wrong is really wrong.”

What’s more, Black Lion is a big public hospital, he said, drawing people from all over Ethiopia. Accordingly, he said, the amount of pathology seen in MRI patients was astounding.

“In the U.S., we may see one abnormal case for every 50 or so scans,” he said. But at Black Lion “it is just the opposite. There is a normal one in every 50 cases.”

The number of people served also surprised Pierce: “One day, we scanned 34 patients.”

At The Corvallis Clinic, Pierce said, technologists usually scan about a dozen people per day.

After a few days of service, though, the scans had to stop. The MRI system works by burning images to CDs, which are taken to a different room to be read. All the images must be permanently stored, however, and at one point the hard drive filled up and nothing could be done until a portable drive could be located.

“It would be helpful to have some of these critical but relatively inexpensive items on hand,” Pierce wrote in his report, noting that “medical supplies such as tape, cotton and alcohol are also in short supply.”

Ditching the CD method and completing the installation of a more efficient one known as PACS – picture archiving and communication system – was among the recommendations in Pierce’s report. Other recommendations include addressing a spatial safety concern in the screening area, developing printed training materials, and determining a certification process for technologists and the department overall.

“My Friends Forever”

Unfortunately, since the autumn, Pierce has not been able to communicate much with Black Lion to check its progress. A state of emergency declared by the Ethiopian government has severely limited contact with staff. According to a recent report from Human Rights Watch, the action “permits arbitrary detention, restricts access to social media and bans communications with foreign groups.”

Nonetheless, Pierce remains committed to the project and believes things will continue to move forward at Black Lion. He welcomes the chance to return and continue to help.

“These are people who will be my friends forever, whether or not I ever return,” he said. “I am looking forward to a continued long-range relationship professionally and personally.”

Asked whether there’s an overarching lesson he learned on the trip, Pierce replied: “We are all alike, no matter where we are or where we come from. Each day we strive to make our lives, the lives of our children and the lives of those around us better than the day before.”

For more information about Ethiopia or RAD AID International, contact Bart Pierce at bartpierce@rad-aid.org.